-

Google does not get privacy

Sundar Pichai, CEO of Google, in an interview with Walt Mossberg at Recode’s Code Conference 2016 1:

We want you to be able to tell Google: maybe the last four hours, just take it off and go off the record. […] you can switch on in-cognito mode. […] I want to save every conversation that I have with my daughter for eternity […]; but some other converations, […] maybe with my general council at Google, I want to be private.

Google has a binary view on privacy. Things are either on the record or off the record—with the default being the former.

For things that are “on the record”, Google’s terms of service they are very explicit about what they can do with it. Namely:

- You grant them “a worldwide license to use, host, store, reproduce, modify, create derivative works […], communicate, publish, publicly perform, publicly display and distribute such content”,

- and, of course, to “analyze your content (including emails) to provide you personally relevant product features, such as customized search results, tailored advertising […]”,

- and lastly, “this license continues even if you stop using our Services”. 2

But, to many people, privacy isn’t that simple and not binary. Consider the following examples:

- You might keep a journal, which you want to have accessible even many years later.

- Private conversations that you have with your child.

Would you want those things to be “on the record”? While many people trust Google with that data, as Pichai points, it is questionable whether they are fully aware of who is getting what kind of license and access to their content, when they are using their phone or computer.

For people who do not want these things on the record, while still getting the benefit of them being safely backed up and synchronised between multiple devices, Google provides no help; there is no option in between that lets you get benefits of using cloud services but without granting all these rights to Google.

If Google wanted to truly get better at privacy, they would do the following:

- Revise the terms of use and don’t apply the above mentioned license to all the user’s content, but just to content that the user shares publicly or with a certain set of users.

- Make content private by default rather than “on the record” by default.

- Enable end-to-end encryption by default where possible when sharing data between users.

As hinted at in the interview, Google wants to tackle the second point by using machine learning to infer defaults better than using their currently manual heuristics; that’s a good start. They also should do more on email encryption, and they should enable end-to-end encryption by default on their new Allo app—that would bring them on par with iMessage, Whatsapp and, soon, Facebook Messenger. The big one though is the first point; it is possible as Apple demonstrates 3, but it is a shame that Google’s business model gives them limited incentive to follow suit.

-

Longer transcript of what Sundar Pichai said (slightly paraphrased by me for readability):

For me: The onus is on us to give enough value that people trust us. Privacy is something that machine learning and AI at Google will help us to do better. Lots of times, it is hard to do privacy because we rely on manual heuristics and how to go to give you manual controls and settings to do these things. But we do these better. Very soon you will be able to give your name to Google and we’ll pop up your My Account settings and control all of that. About a billion people went through these settings in the last year alone. But all the time we want to get even better, we want you to be able to tell Google: maybe the last four hours, just take it off and go off the record. We can do these kind of things. When you use Chrome, you can use it any way you want, you can switch on in-cognito mode, if you want to; we are doing it the same with the messaging product. We give users choice. All the time, we get smarter to give users sophisticated privacy controls. You know, I want to save every conversation that I have with my daughter for eternity, and because I want to be able to go back, look back and et cetera; but some other conversations, I want to, maybe with my general council at Google, I want to be private. I want to be able to do those things and we want to be smart about it all those times.

-

Expanded extract:

When you upload, submit, store, send or receive content to or through our Services, you give Google (and those we work with) a worldwide license to use, host, store, reproduce, modify, create derivative works […], communicate, publish, publicly perform, publicly display and distribute such content. The rights you grant in this license are for the limited purpose of operating, promoting, and improving our Services, and to develop new ones. This license continues even if you stop using our Services […] Our automated systems analyze your content (including emails) to provide you personally relevant product features, such as customized search results, tailored advertising, and spam and malware detection.

-

Licensing terms for Content in Apple’s iCloud terms (highlight mine):

[…] by submitting or posting such Content on areas of the Service that are accessible by the public or other users with whom you consent to share such Content, you grant Apple a worldwide, royalty-free, non-exclusive license to use, distribute, reproduce, modify, adapt, publish, translate, publicly perform and publicly display such Content on the Service solely for the purpose for which such Content was submitted or made available, without any compensation or obligation to you.

- Tech Note: Lessons from converting complex submodules to Cocoapods

-

Facial recognition of anyone has gone mainstream in Russia 1, reports The Guardian. The FindFace app feeds all the data from a Russian social networking site through an advanced facial recognition algorithm and let’s anyone quickly and easily identify anyone else 2. A big, big loss for privacy.

The founders see themselves just as a wheel in the ever-turning enhancement of technology:

But Kabakov said, as a philosophy graduate, he believes we cannot stop technological progress so must work with it and make sure it stays open and transparent. […]. A person should understand that in the modern world he is under the spotlight of technology. You just have to live with that.”

That’s a convenient view to avoid any moral questions about your work; it also ignores the fact, that, ultimately, technology does not create itself, but people are in charge of creating and adapting technoloy, and steering the economic, political and societal systems.

-

Confirming that large-scale facial recognition indeed isn’t far from facial detection. ↩

-

With a 70% success rate. ↩

-

-

In the past there has been a lot of debate about the potentially kill-all-humans dangers of Artificial Intelligence. Sparked by Nick Bostrom’s book Superintelligence, which provides an concerning and detailed description, the likes of Elon Musk, Stephen Hawking, Steve Wozniak and many AI researchers have voiced their concerns — for an easily accessible overview, I recommend Wait But Why’s two-parter.

Is it all doom ahead? Ben Goertzel, who is actively working on creating a super-intelligence with his OpenCog project, is arguing otherwise. His response is a long, well-written read, and worth it to get an understanding of the side of AI optimists.

The main arguments that stood out to me were:

- A super-intelligence will likely continually re-evaluate and re-adjust its goals, so the initial goal is not nearly as critical and likely to cause doom as Bostrom makes it appear. Also, he rejects that intelligence and goals are orthogonal, i.e., he argues that it seems highly unlikely for a super-intelligent system to adopt and stick with a “stupid” goal such as filling the universe with paper clips.

- Utility maximisation is overly simplistic and unlikely to work well for a super-intelligence. Compare to how little human goals and behaviours align with utility theory, even when looking at it just in economic terms, and how poorly Utilitarianism works as an ethical framework to decide what’s right.

- It could be less of a case of us-versus-them when humans create a super-intelligence and rather a convergence of the two, where humans create the super-intelligence in a way that benefits them and where it’s not clearly distinguishable what is human and what is the super-intelligence.

1 and 2 are reasonable points, and 3 showcases the potential benefits (which Bostrom also acknowledges but doesn’t focus on).

I find Goertzel’s view particularly interesting as he takes Bostrom’s feedback less philosophical and looks at it more in a practical way. Goertzel is actively working on his approach to a super-intelligence and he’s optimistic that it’s just a decade away. As such, he’s arguing for his open approach which is not compatible with Bostrom’s recommendation that work on creating a super-intelligence shouldn’t be done in the open, should be regulated and ideally be done by a small, isolated group of selected scientists.

-

Graham Lee (via Ole Begemann):

All of this represented a helpfulness and humility on the part of the applications makers: we do not know everything you want to do. We do know some things you might want to do: we’ll let you combine them and mash them up – “rip, mix and burn” as they used to say – making you more satisfied and our stuff more useful.

And in a follow-up on the paradox of scripting:

The message given off by the state of scripting is that scripting is programming, programming is a specialist pursuit, therefore regular folk should not be shown scripting nor given access to its power. They should rely on the technomages to magnanimously grant them the benefits of computing.

Letting users combine individual applications and web services can unlock the power of computers as a bicycle for the minds. Imagine the impact this could have if it was intuitive for a larger audience than just programmers1.

-

Automator, Yahoo Pipes (RIP), IFTTT, Workflow are steps in the right direction. ↩

-

- Tech Note: Upload rejected due to CFBundleResourceSpecification

- Tech Note: Custom transitions for pushing container view controllers

-

It used to be simple: viruses don’t count as being alive as they just piggy-back on cellular life. This episode of Radio lab provides a fascinating glimpse at newer discoveries which show that it’s not that simple. Some viruses might have evolved—seemingly backwards—from cellular life.

-

Secure your mails

Ever read a post card that wasn’t meant for you?

Without encryption, emails you send and receive are as easy to read as post cards. They could barely have less security, as they are transmitted in plain text. This means that any computer between yours and the recipient’s can study the mails in full without much effort. Encryption prevents your email provider (e.g. Google or Yahoo) from seeing and analysing your email content.

Similarly, even if you receive a mail from steve@apple.com, that doesn’t mean that you got a (delayed) email you can brag about - spoofing senders is easy as there is no process to verify the sender. Signing your emails allows the recipient to gain much more confidence that the email was indeed sent by you - rather than someone else pretending to be you.

This is, unless you sign and encrypt your emails. To me, this is not only a matter of security, but also of executing my right to privacy.

Don’t worry, I’m using HTTPS

Using https is a first step, but not the same. HTTPS makes sure that no one between your client and your email provider can intercept your mails, but it still means that your email provider has access to the content of all your mails.

It also does not help much in terms of securing the long trip from your email provider to your email’s recipient. With email encryption, only you and the recipient1 have access to your email content - your email provider does not have access to it.

Because of that, encrypting emails has one gotcha: you can’t use webmail as it would require your email provider to have your private keys which is a big no-no and besides the point of encrypting your mails in the first place. Make sure you are okay with.

How it works (the technical stuff)

The most common practice for encrypting your emails is using a combination of public and private keys. Basically, you use a signed mail which includes information for the recipient on how to send you encrypted mails - which only you can decrypt (using the private key). It’s like every mail you send comes with a secure return envelope that has a lock which only you can open. If someone sends you a mail, they put the message in the envelope and lock it (i.e., encrypt it using your public key), then send it along the unsafe path of regular email2, and you’ll be able to recreate the original message by decrypting it with your private key.

Check out this nice visualisation using LEGOs (click on it to play the video):

I’m sold. How do I secure my emails?

The mechanism that I’ll walk you through is called S/MIME3 which is similar to securing websites by using HTTPS. Yes, there’s also PGP (and its open-source equivalent GPG) but that is not supported out-of-the-box by most devices and requires additional software4.

Important: If you have more than one email address, you will set up certificates for each of them individually. It should take about 5 minutes to set up the certificates for each email address, depending on the number of your devices. Totally worth it!

Note: The method I’m describing here is for Mac and iOS. It should be similar for other operating systems, but I haven’t tried.

1) Get a certificate

First you need a certificate for your email address: Comodo issues email SSL certificates for free for private use which worked well for me on my iOS 7 devices and Mac OS X 10.9. In Comodo’s Application form, make sure you put in the email address that you would like to have encrypted.

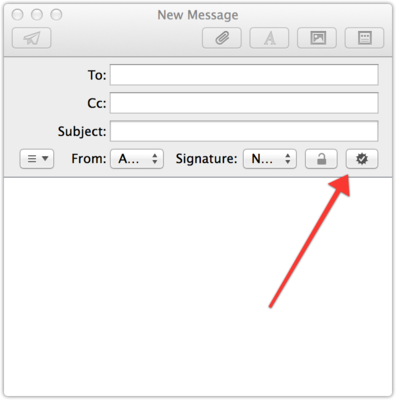

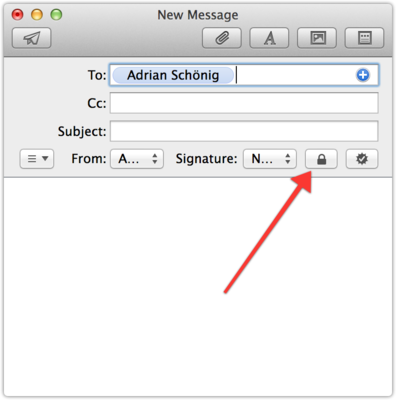

Once you have downloaded your certificate, add it to your Keychain Access. Make sure it shows up in the “My Certificates” category. Mac’s Mail app will now pick it automatically and you’ll get a new set of icons when composing a new message (you might have to restart Mail app).

Signed (no encryption possible)1b) Distribute it across your devices

For iOS devices to the following:

- Open Keychain Access on your Mac, select the certificate (“File” > “Export Items” > “Save”). Make sure file format is set to “Personal Information Exchange (.p12)”, then provide a password.

- Transfer it to your devices, e.g., by emailing it which is fine as long as you picked a strong password.

- Next, install it on your devices by opening that attachment, entering the password and tapping “Install”.

- Finally, add it to your email accounts by opening the Settings app and selecting “Mail, …”” > choose your account > “Account” > “Advanced” > “S/MIME”: enable the section and then enable “Sign” and “Encrypt” by picking the right certificate.

2) Send signed mails

Now you are set to sign emails, which means you can send out your secure return envelopes and you are ready to receive encrypted mails.

3) Sending encrypted messages

To encrypt a message, your recipient needs to do the same thing and they need to send you a message, so that you have their signature (“secure return envelopes”) and can send them encrypted mails.

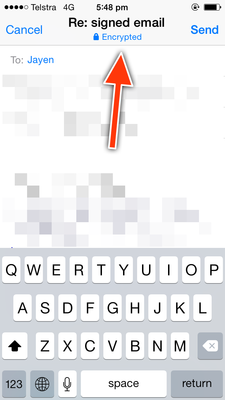

iOS

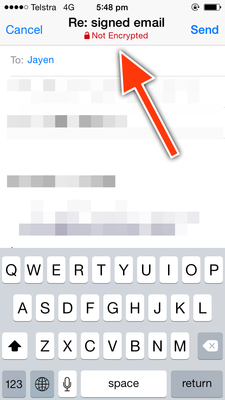

At first, emails won’t be encrypted as you need to verify and install the certificate of the person who you want to send an encrypted mail to. If you receive an email from them, watch out for the little checkmark next to their name. Tap their name and install the certificate and your emails to them will then all be encrypted:

Not encrypted. Meh.

A signed and encrypted email

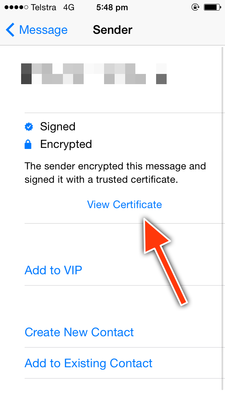

After tapping the sender's name, select 'View Certificate'.

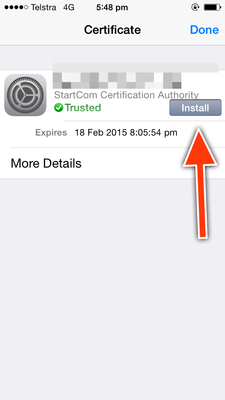

Installing the certificate

Email encrypted! Hooray!Mac

Mail.app on the Mac is installing certificates automatically, as long as they are is from a trusted source. If not, you’ll see a warning on top of the mails and you can manually verify the certificate and set it to “trusted”.

At first I had some issues which were, apparently, caused by my own certificate coming from an untrusted souce (StartSSL, which is quite popular). I couldn’t get Mail.app to encrypt any emails that I tried to sent. I switched to a different certificate authority, Comodo, and then encrypting my emails went smoothly.

Writing an encrypted and signed email in MailOther operating systems

Android, Linux, Windows, Windows Phone

Limitations

- You now rely on the recipient to do the right thing and to not redistribute the decrypted content. Say, if you receive an encrypted mail, decrypt it and then forward it to someone else without re-encrypting it, the encryption is lost and what was so carefully encrypted before is now out there in plain text again.

- You need to protect your devices which have the private key, so make sure you have a passcode or password or have your fingerprint sensor or retina scanner enabled.

- If you use IMAP, don’t store drafts on the server as those will not be encrypted5.

- Don’t give out your password, make sure it’s one that’s hard to guess, don’t use the same one everywhere, and use 2-factor authorization if possible.

- Of course, watch out for people looking over your shoulder.

- As mentioned above, you won’t be able to use webmail with your encrypted emails.

One last step

In order to make the most out of your encryption, tell your friends, ask them to send you a signed mail, install their certificates, and you can communicate securely and without having to worry about who might be spying on you.

Further reading:

- Secure emails with Apple Mail

- Limitations of secure email

- What Is S/MIME Email and Why Should I Be Using It

-

Well, only your and your recipient’s devices… ↩

-

Still visible to everyone would be whom the mail is addressed to, who sent it, what the subject is and that it’s full of encrypted garbled content. ↩

-

S/MIME stands for Secure/Multipurpose Internet Mail Extensions and, of course, there’s a Wikipedia page for it. ↩

-

I’m using Mac and iOS devices which support S/MIME out of the box while they’d require special plug-ins or apps to work with PGP. ↩

-

Emails that you send and receive that are encrypted will be stored encrypted on your IMAP server - only your client will decrypt them. That means you need to make sure you safeguard and keep your keys, otherwise you won’t be able to read old emails. ↩

-

“The key for Cara is that they’re doing face detection, not recognition,” says Natalie Fronseca, co-founder and executive producer for the Privacy Identity Innovation tech conference, who is very familiar with Cara. “Jason does privacy by design, and that will help him avoid the adverse consequences that often come with data collection.”

It’s only a small step from going from face detection to recognition, and by classifying faces by characteristics (gender, wears glasses, colour, etc.) you can even use detection data to recognise/track individuals.

Inevitably, we will move towards a world where public cameras not only watch us, but software systems actively analyze what we’re doing and what we look like — and actively share this information with businesses and other citizens.

The problem comes when you share this information with businesses and when you don’t have control anymore over who’s tracking you. Since it’s someone else watching you, you don’t have that information by definition.

Compare that to self-trackers such as Fitbits, Google Latitude and similar. You provide the data, rather than someone watching you and inferring things from that.